Jerry's map

/Article and photographs by Gail Anderson

This article was originally published in issue 12 (January 2012) of UPPERCASE magazine.

Video by Greg Whitmore (2009).

Jerry Gretzinger is a musser. "My mother called me a "musser" because I liked to mix things together," he says. "I once mixed ammonia and Clorox and then took a whiff. I invented games and forced my younger brother to play them, and then got pissed off when he won." Many of Jerry's games had their basis in maps, with fully operating railroads, airlines, and hotels. There were armies and wars. But saying that Jerry's maps have become considerably more involved since his Michigan childhood is a bit of an understatement. In fact, he's been chipping away at the same map since 1963, though he did take a break to raise a family. The map is now made up of over 2400 individual 8x10 sheets.

An example of one of Jerry's panels.

"The map began as a doodle," Jerry says in Greg Whitmore's 2009 documentary trailer — a sudden viral hit on Vimeo with almost 100,000 hits. "I just made little rectangles and crosshatched them carefully." Using typing paper allotted by his mother sparingly, Jerry began to create a city, and soon, countries with their high-speed monorail lines, freeways, and void defense walls (more on the "void" later). With each new panel, Jerry's world expanded.

The detail of one particular panel.

"Not only does he build his world, he also destroys it," a Vimeo fan writes on Jerry's page. "What I found most fascinating about this was that my preconceived ideas of what he was doing changed every 30 seconds as I discovered just how deeply into his world he got." Jerry is into his world in a big way, with over 2400 completed map panels methodically categorized on metal shelves. The stacks represent almost a half-century of evolution in his virtual world.

Jerry, 69, begins each day in his Cold Spring, NY basement with some early morning map time. He and his wife, Meg Staley, are working on their next life chapter, having sold the clothing company they created together, Staley/Gretzinger, about seven years ago. They divide their time between New York and their 100-acre working farm in Maple City, Michigan, where Jerry tends to sheep, goats, chicken, and turkeys. "I don't feel deprived in the least without television when I'm at the farm," Jerry says as I clutch my chest in horror. "I get pretty unplugged when I'm out in Michigan. I'm in the garden a lot."

"When I first met Jerry he was living with my sister in an illegal loft in a former thread factory in SoHo," Jerry's sister-in-law, artist Lynn Staley recalls. "The venue itself was unconventional enough, but Jerry was in the process of papering the long hallway leading to the living space with bits of torn New Yorker magazines. Not the pretty covers, mind you, but the black and white text pages punctuated by an occasional cartoon. You'd be talking to him and he'd be papering, homemade paste pot in hand, as if it was the most normal thing in the world." I met Jerry through Lynn in the late 1980's, and was completely taken by his good humor and eccentricities. But I had no idea about the map until only this past summer. And now, even Oprah's a fan since it was recently featured on her website — the ultimate seal of approval.

Organized paints, with the colours and dates indicated on the cap.

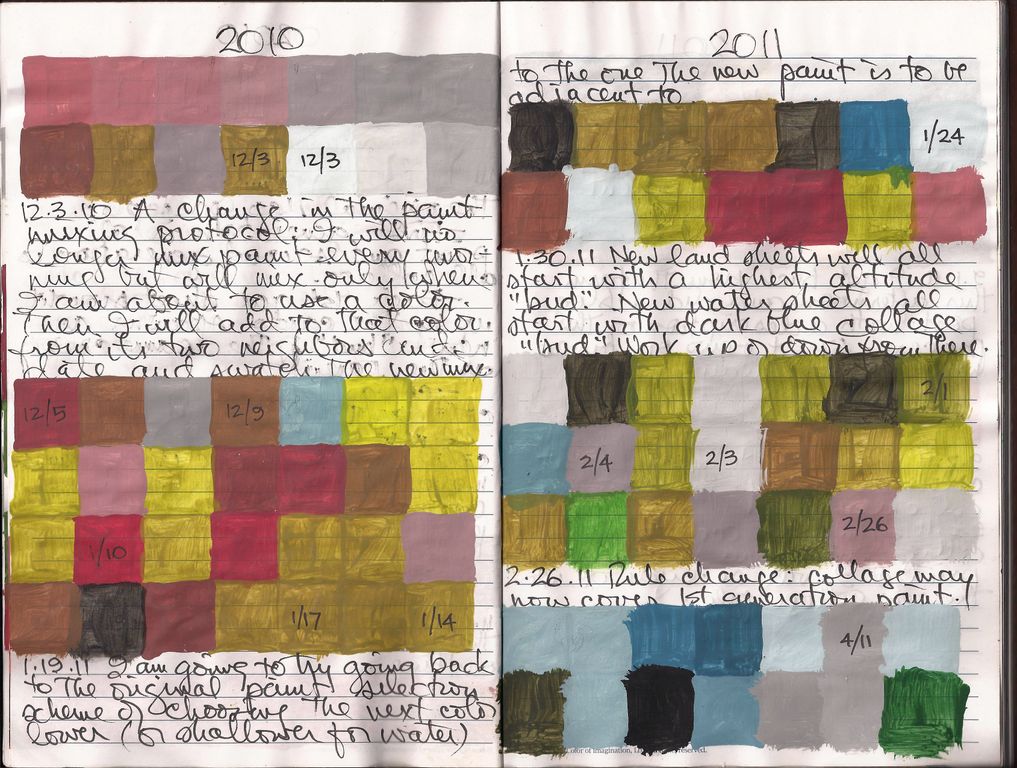

Each morning before sunrise, Jerry re-tints his colors. Two rows of small plastic bottles are lined up in sequence on a large table in the dark, low-ceilinged basement in the Cold Spring, NY, house that he and Meg share. Jerry listens to music on Internet radio as he begins his morning ritual, adding notes and sample chips to a massive, one could say, "obsessive" color journal. Next, Jerry draws a card from the bottom of a deck of elaborately retooled playing cards that dictates how many panels he moves in the rotation; which panel will be worked on next. There is mind-boggling ritual involved in every step — logging elements into a spreadsheet in now-obsolete HP software on a computer that's missing part of its case. "The housekeeping takes so much time that the execution suffers," Jerry says with a smile. One day, he's scanning and reworking an archival page, and the next, he's forming parts of a new world.

"I love the interplay between what's out there and the map," Jerry says. "Anything goes. Yesterday, my little cheap printer was running out of ink and was giving me totally mis-colored prints. Still, they get incorporated into the map. Then, my younger grand daughter scribbled on one, and that became part of it. I encourage people to touch and feel the map, and not to be shy."

Jerry started using his most recent cards around 2003, though the system dates back much earlier. He is protective of maintaining the cards’ order, and seemed slightly concerned when I had them on the table. They are as beautiful and quirky as the map itself.

One of the most intriguing aspects of Jerry's map is the structure and rules he imposes on his virtual world, complete with implications of destruction. For example, there's a "void" card. When Jerry draws it, all bets are off — entire countries are sometimes wiped out, and new worlds emerge from the ruins. The ritual appears to have been created to expunge Jerry's own creative process; he becomes simply the executor of the cards' fastidious dictations rather than the architect of a vast universe. The randomness of the card's instructions helps Jerry maintain the vitality and evolution of his world, and/or can lead to its destruction. By contrast, many outsider artists attempt to compensate for their lifelong instability by constructing a comprehensible world that is completely fictitious. What Jerry Gretzinger has done instead is to build in the possibility of total destruction to his virtual world, which actually makes it beautiful.

"Jerry's willingness to bend, adapt and break his own rules extends freedom to the map itself," says filmmaker, Greg Whitmore, the creator of Jerry's documentary trailer. "I should add that though Jerry is permissive and liberal when it comes to the process, he is dogmatic in one regard: that this 'thing' is, in fact, a map and he is responsible for it."

Jerry is able to abandon himself to the randomness of his map, which, ironically, he's designed himself, choosing all of the variables. For example, a limited color palette means that there can only be a certain amount of disharmony. In aggregate, the work is remarkably integrated, and therefore breathtaking in its scope. And it's just a little crazy — but that good, quirky crazy that you can't help but love.

The map has never been displayed in its entirety*, and no one, not even Jerry, knows what his world looks like. "Even he is powerless to say what the outcome will be," says Lynn Staley. "So not only is there great beauty in the map's texture and variation, there is potentially galactic suspense. Will this place, whatever it is, survive or be consumed by the void? What about its inhabitants? And what can we learn from it about our own fate? Is there someone somewhere with another deck of cards like Jer's?"

*This article was originally published in issue 12. The Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art has been preparing to mount an exhibition of the project, A Half Century Project of Imagination, on view October 5–14, 2012.